Covid-19 tracing Apps: Big brother is not watching you

18 November 2021

Digital contact tracing systems.

The strong impact of EU law in the field of data protection is a topic of crucial interest when it comes to the development of a digital tracing system to combat the pandemic.

Tracing applications were initially considered as a key instrument for “a quick exit out of the crisis” and quite rapidly sparked a lively debate as to their intrusive nature and their possible use by States to track down citizens. Could digital tracing systems be considered as a threat to citizens’ fundamental rights? What lessons could be learned from such developments? How could they potentially evolve in the future?

This moving context drew the backdrop for a group of researchers from Research Luxembourg and the University of Rome 3, under the project LEGAFIGHT, to make recommendations on a draft legislation on tracing applications for Luxembourg.

Understanding what lies behind digital contact tracing Apps

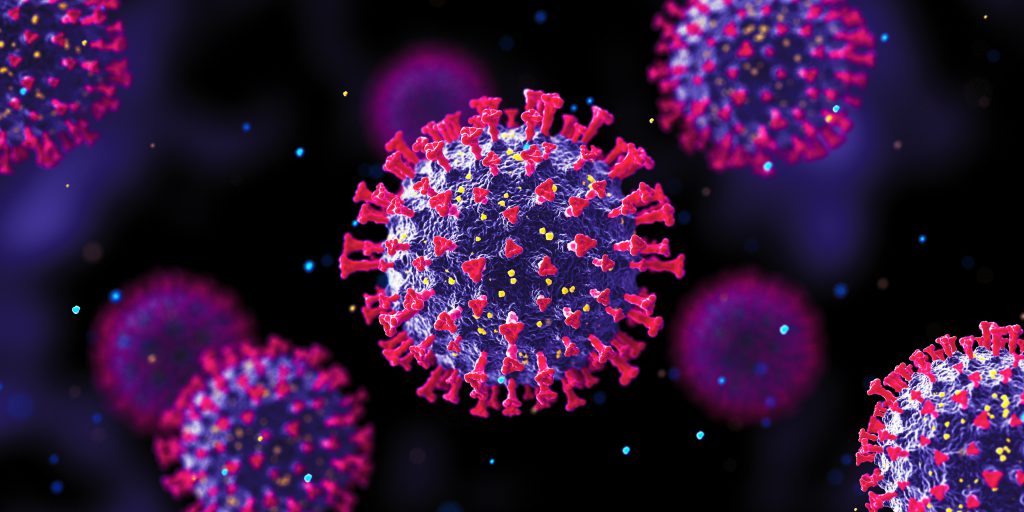

The outbreak of COVID-19 led countries to take various measures to reduce the spread of the infection.

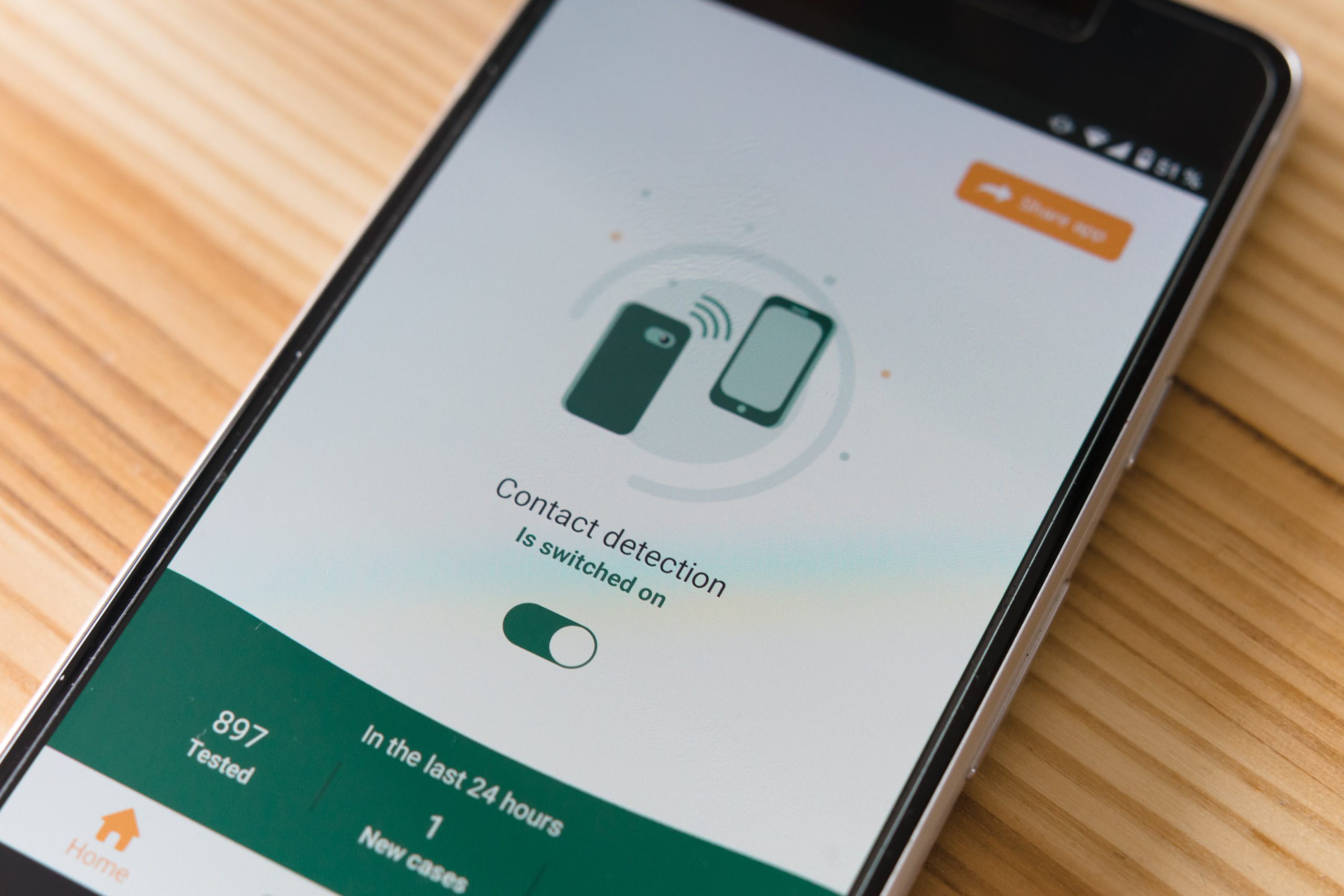

One of these measures relies on the fact that new smart phones feature powerful sensors. Using Bluetooth Lower Energy technology, a phone can detect short-range power signals from other phones, identify them and estimate the distance and duration of the encounter.

With some extra information, an app can estimate whether there has been a risk of infection. Digital contact tracing (DCT) works in such a way. They alert the user when they have been in close proximity to a person who tests positive for the virus. As the user is at risk of infection, they are advised to test for COVID19 and, if they also test positive, to self-isolate and reduce the spread of the virus.

An application using GPS, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth antennas can receive and process signals and track not only the user’s movements but also whom they meet.

As soon as the idea of using DCT emerged, many people began to worry about privacy.

One concern relates to the access permissions that DCT applications may require, e.g. contact details, call history, internet searches, camera permissions, access to call records, messages and mobile media. Another concern is where the data, including location traces or contact history, is stored and processed and how it is protected from unauthorised access.

Depending on the implementation and the underlying communication and data management architectures, DCT applications offer different security guarantees. Overall, most of today’s applications are, to different degrees, privacy-preserving.

GDPR to the rescue

While breaches of privacy may occur, and despite insights from describing attack scenarios, not everything that can happen will happen.

When assessing the risks, there are other factors to keep in mind. Laws and regulations, for example, impose restrictions on the processing of personal data and hold accountable those who pursue malpractices.

In Europe, where above all the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) states that data processing can only take place under strict requirements, countries have been free to choose their DCT, albeit following EU guidelines.

EU guidelines include

- Contact tracing and warning Apps should only be voluntarily installed and used;

- The data minimisation principle should be employed in the app design;

- Apps should use proximity data based on Bluetooth technology;

- No location data is requested or utilised by the tracing App;

- Contact tracing and warning Apps do not track people’s movements;

- The data should not be stored longer than necessary – 14 days;

- Data should be protected through state-of-the-art techniques, including encryption;

- The applications should be de-activated as soon as the pandemic is over.

The GDPR is the most appropriate legal basis for the legal framing of tracing applications. The fact that the processing of data for objectives of public interest should also be assisted by a specific normative basis under European or national law should not be considered as a superfluous legal requirement but, on the contrary, as an opportunity to clearly define the limits of the use of data as well as the entities that will act as the controller as per the GDPR requirements. The existence of a specific act also guarantees transparency of the system and represents a strong signal coming from the legislature as to the importance granted to the respect of citizen’s fundamental rights.

The very protective approach of individual’s privacy, which is the essence of the GDPR, proved to be a very efficient

In the end, this project succeeded in demonstrating that all the legal frameworks examined have shown that the legal instruments adopted successfully protect users’ rights.

Tracing Apps are dead, long live tracing Apps!

With new waves looming on the horizon, the pandemic is going to last. Tracing applications may stay longer with us than originally thought. Reshaped into multifunctional applications, transformed into digital certificates supports (for PCR tests or vaccines), the newly born sanitary applications may prove eventually useful in the eyes of the public and perceived less intrusive. Besides, the emergence of a new state of mind, that of “pandemic-fatigue”, could lead to a better social acceptance of such tracing and informing systems. Finally, tracing applications are just one of the many configurations of e-health systems.

Any development concerning digital tracking or e-health devices should be supported by a thorough sociological study to understand how to improve the social acceptance of these systems.

This research is the result of a common endeavour. The various parts have been written by Gabriele Lenzini, Interdisciplinary Centre for Security, Reliability and Trust of the University of Luxembourg; Elise Poillot, University of Luxembourg; Giorgio Resta, University of Rome 3; Vincenzo Zeno-Zencovich, University of Rome 3; Damien Negre, University of Luxembourg.

The project received support from the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR) in the frame of the Covid-19 research funding scheme.

Read the publication, entitled Data protection in the context of COVID-19: A short (hi)story of tracing applications