COVID-19: How can our psychological reactions during this pandemic, and in particular towards the vaccine be explained?

11 March 2021

The COVID-19 pandemic imposes a high level of stress on all of us and negatively affects our mental health.

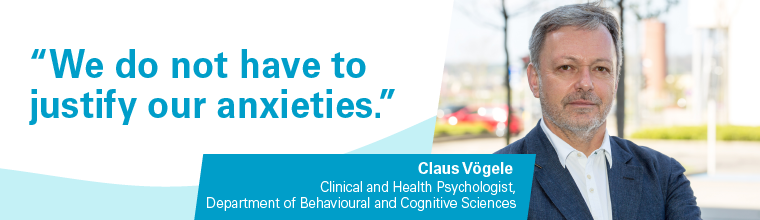

How can our psychological reactions during this pandemic, and in particular towards the vaccine, be explained? Prof. Claus Vögele, Clinical and Health Psychologist at the University of Luxembourg, elucidates peoples’ psychological reactions– and underlines that we do not have to justify our anxieties.

This article was originally published by the University of Luxembourg

What are the effects of the pandemic on mental health and how can a vaccine alleviate them?

Not surprisingly, we have seen an increase in perceived stress, loneliness, anxiety and depression over the last 11 months, in Luxembourg but also globally, as shown in our ongoing survey across 6 European countries. This increase is most certainly a combined effect of the uncertainties caused by a potential or actual SARS-CoV-2 infection and its effects on health, but it can also be influenced by the social distancing measures designed to curb the increasing rates of infection.

The beginning of the vaccination brings hope, for the first time since the start of the pandemic, that we might be able to return to a certain level of normality at some point this year. I would expect this to have a positive effect on how people feel, even before they get the vaccine.

How did the perception of the pandemic and of the measures put in place develop over time?

What we can see in the media these days is an increasing percentage of the population getting tired of the whole situation, which is completely understandable as the pandemic imposes a lot of stress on all of us. In comparison to spring 2020, people are less willing to adhere to the protective rules which were put in place, they have not much patience left. In this context, the availability of vaccines is very good news as it eventually offers the possibility to end all the restrictions that are in place to stop the spread of the disease, at least in the foreseeable future.

At the same time, we also see that people observe very closely what is happening in politics. The messages that politicians send out have a clearly visible impact on attitudes and behaviours in the population. The pandemic is a very dynamic situation, as a consequence of which messages may have been perceived as contradictory, and this also concerns information on vaccination.

In terms of reaching large parts of the population in the context of a vaccination campaign, it is important for policy makers to understand the complexity of the relationship between emotions and the aim to increase preventive health behaviours. A message intending to increase the perceived social responsibility by taking the vaccine, for example, may backfire by inducing feelings of guilt or shame, which result in the opposite than the intended action.

Therefore, it is important to acknowledge fears, anger and other negative emotions while at the same time emphasising the stringent safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines.

Still, quite a few people seem to be concerned about the vaccines. Where could this insecurity on vaccines come from?

The most frequently expressed argument against the COVID-19 vaccines relates to the speed of their development. It is mostly asked how a safe and efficient vaccine can be produced in such a short time whereas vaccine development usually takes up to 10 years. Well, the short answer is: It is possible through the combined effort of all researchers, medical professionals and companies involved.

The persistence of this mistrust against the ability to significantly speed up such a process is deeply rooted in widespread anxiety, feelings of loss of control, and psychological fatigue caused by the pandemic. This can also negatively affect protective health behaviours and, therefore, vaccination intentions.

Can you give examples of such concerns or anxieties?

One argument often used by the opponents of vaccination is the occurrence of side effects. Here, it is important to remember that there is no effective medical intervention without side effects. In fact, it is highly unlikely that any side effects occur after more than 48 hours after injection, my colleagues already addressed this topic in their interviews. There is also the misperception by some people that vaccination is related to death events. These people confuse a temporal association with causality. It becomes clear when looking at the clinical trials: In some of the placebo-control-groups, even more people died compared to the vaccinated group– which is a natural phenomenon and has not at all been shown to be related to receiving the vaccine.

At the same time, making causal connections when there are only temporal coincidences generally is something deeply rooted in our minds. From an evolutionary point-of-view, this has been a successful strategy for survival for thousands of years to try and predict what might be happening next. Nevertheless, looking at the scientific figures can help us to better understand and assess the real danger, which is the virus itself.

How does the anxiety about vaccines relate to people’s everyday behaviours?

The important difference between vaccination and exposing oneself to a potential infection is the fact that the former is a medical intervention. It may be understandable that for some of us allowing foreign agent such as a vaccine to enter our body is somewhat different to our everyday behaviours and habits. On the other hand, walking in the street and catching SARS-CoV-2 might just be perceived as bad luck, as no active action was involved, and it was probably not even noticed. Another example: Excessive smoking or drinking alcohol is also known to have a negative impact on health, still we might find such behaviours even rewarding because it might take away anxiety for a certain time.

People often have anxieties regarding the efficacy of a vaccine and its potential side effects. Probably no one likes the feeling of getting an injection, this is why anxieties in this context should be understood as an entirely normal reaction. There is no need to justify it, but what can be done is to look at the many valid reasons why it still makes sense to receive the vaccination. Anxiety and panic are always bad counsel, you should use your reason.

Still, there are many myths around vaccinations, which all have been debunked but unfortunately also resuscitated in the current coronavirus-crisis. Such conspiracy theories somehow voice the anxiety of many people, thereby creating a feeling to be part of a group, which is a basic need of all of us. It is, therefore, important to acknowledge one’s own anxieties but at the same time to consider the facts. I strongly feel that people should not forget how many deaths and illnesses vaccines have prevented, and how they continue to protect us from potentially devastating forms of infectious disease.

Does this mean that understanding the importance of vaccinations can also help to overcome the anxieties?

Well, we can’t promise that vaccines are going to release people from all their anxieties. But what we can say is that as a matter of fact that they protect against a very infectious – and for many deadly – disease with very high efficacy. The distancing measures which have been put in place now also induce anxieties, loneliness and depression in many people. Especially for those who are living alone or are in retirement homes, this becomes more and more serious. Therefore, social distancing measures cannot serve as a long-term strategy or alternative to vaccination as they only partially slow down the spread of the virus without inducing immunity. If we manage to vaccinate a sufficient proportion of the population, there will be little need to extend these measures for much longer.

Claus Vögele is a full Professor in Health Psychology and Head of the Department of Behavioural and Cognitive Sciences at the University of Luxembourg. His main research areas include Clinical-, Health- and Biological Psychology, Psychophysiology and Behavioural Medicine.

This article was originally published by the University of Luxembourg