Babies and their gut microbiome tell a story

05 April 2021

Thanks to a long-standing study – called COSMIC – a Research Luxembourg team highlight lasting birth mode-dependent differences and their association with immune function.

In a recent scientific publication, researchers from the Luxembourg Centre for Systems Biomedicine (LCSB) and the Department of Life Sciences and Medicine at the University of Luxembourg address the knowledge gaps concerning the lasting effect of birth mode on infants. Thanks to a long-standing study – called COSMIC – they highlight differences in the gut microbiome composition and function that persist throughout the first year of life. These birth mode-dependent alterations are likely to affect the status of the immune system and antimicrobial resistance in the long run. The results of the team led by Prof. Paul Wilmes are published in the open-access journal ISME Communications.

The rate of caesarean section delivery (CSD) is constantly increasing worldwide, especially in Europe where it represents 25% of births. Although several studies, including previous ones by the same team of researchers, have shown that CSD affects both the gut microbiome and the development of the immune system in new-borns, the lasting impacts of birth mode are not well understood.

“Current hypotheses are that caesarean section is linked to different chronic diseases later in life, including metabolic disorders and allergies, or may facilitate the development of antimicrobial resistance,” details Prof. Paul Wilmes, head of the Systems Ecology group at the LCSB.

However, studies over longer periods of time are needed to determine the continuous effect during the first year of life which represents a critical window of development.

The Systems Ecology group has been investigating the impact of vaginal delivery (VD) and caesarean section on babies for several years together with Prof. Carine de Beaufort from the Pediatric Clinic at the Centre Hospitalier de Luxembourg (CHL). They have previously identified differences in the structure and function of the babies’ microbiomes. Building on this long-standing interest, they assessed the pervasive effect of birth mode through an in-depth longitudinal analysis ranging from immediately after birth until early childhood.

“We followed VD and CSD new-borns, collected faecal samples at crucial intervals – from 5 days to one year – and performed high-resolution metagenomic analyses of the gut microbiomes of these infants,” explains Dr Susheel Bhanu Busi, co-first author of the study. “We also used PathoFact, a new bioinformatics tool developed in-house, to identify genes that encode virulence factors or antibiotic resistance.”

The results highlight lasting birth mode-dependent differences and their association with immune function.

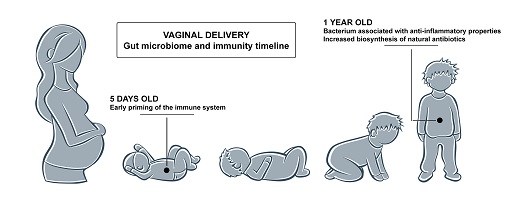

While the long-term study shows that gut microbiomes of CSD and VD babies become more similar over time, it also points out differences – in terms of composition and function – in one year old infants delivered vaginally.

For example, a bacterium, called Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, is more abundant in the VD group. It is usually associated with healthy human microbiomes and could confer anti-inflammatory properties. A functional analysis of the microbiomes also indicates an increase in the biosynthesis of natural antibiotics for the same group.

“Both results suggest that colonising microorganisms in the gut play a crucial role and that VD children could benefit from early resistance mechanisms against opportunistic pathogens,” co-first author Laura de Nies underlines.

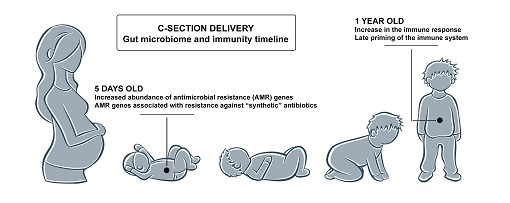

Combining new results with their previous studies on the topic, the LCSB researchers also confirmed that a reduction in early immune system priming in new-borns delivered by caesarean section might lead to persistent effects throughout the first year of life. These may in turn explain the higher rates of immune system-linked diseases observed in CSD infants later in life, including metabolic disorders and allergies.

Next, the team of Prof. Wilmes investigated how birth mode modulates antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and found that caesarean section is associated with genes conferring resistance against synthetic and semi-synthetic antibiotics as early as five days after birth.

He explains: “As mothers undergoing the surgical procedure are administered antibiotics, it is plausible that this enrichment in AMR genes is linked to the hospital environment and the caesarean section.”

Prof. Paul Wilmes

The study also provided some insights into the role of mobile genetic elements – such as plasmids and bacteriophages – in conferring antimicrobial resistance, showing that they are key contributors to the establishment and persistence of AMR throughout the first year of life, irrespective of birth mode.

Collectively, these findings suggest that birth mode-dependent effects still remain after a year. The early impact of caesarean section delivery on the establishment of the gut microbiome of new-borns leads to persistent structural and functional differences. They affect the immune system, defence mechanisms against pathogens and antimicrobial resistance.

“This study highlights the importance of following these effects over extended periods of time and paves the way for future interventions aimed at restoring key functional features of the microbiome in CSD infants,” concludes Dr Busi.